Soil, sand and water have always moved on the landscape. Rivers rise, fall and change course. They shape the places where we live, and even the ways we live.

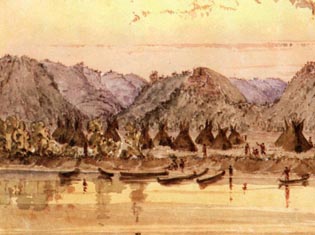

But soil, sand and water have not always moved so far and so fast. Before European settlement in the mid-1800s, water ran in streams more steadily throughout the year, rising and falling with heavy rains but not as drastically as it does now. At that time the Whitewater River straddled one of the richest landscapes in North America—the transition zone between eastern hardwood forests and western tallgrass prairies. In those diverse plant communities more water naturally evaporated into the air, seeped slowly into the earth, and soaked into the thirsty roots of native plants. The people who lived here respected the cycle and lived within it.

Well-intentioned European farmers and business people removed the vegetation to build roads, towns and cultivated fields. Without vegetation, the water cycle changed. In 1938 the Whitewater River flooded 28 times. Fields and homes in valleys were buried under more than 15 feet of sand and silt, and once-prosperous towns of Beaver and Whitewater Falls were buried and abandoned.

In the 1920s, when flooding was severe, seven Winona men planted willows at Garvin Brook to reduce erosion at the arches near Highway 14.

Some saw what was happening and became leaders. The Izaak Walton League’s first chapter was established here, fighting for the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife & Fish Refuge and working for clean water legislation. The federal government’s first soil conservation program, started just across the river in Coon Valley, Wisconsin by Aldo Leopold in the 1930s, was quickly replicated in our watershed. Farmers stepped up to try new practices, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) helped build terraces and other structures. Erosion slowed and streams stabilized.

In 1987, concern about massing sediment at the confluence of the Whitewater and Mississippi Rivers brought landowners and local, state, and federal conservation staff together to look at upstream sources. A successful erosion reduction project on the Middle Whitewater River led to more opportunities, so the Whitewater Joint Powers Board formed in 1989 to facilitate collaboration between Olmsted, Wabasha, and Winona Counties and others.

A small army of people have continued to be aware and to work for healthy streams and clean groundwater through the decades, integrating sound farming, city planning, business and home practices into community life. But much work remains. How will we improve water quality, community and our daily lives? What will we leave behind?

Learn more about our region’s conservation story and see historic photos.